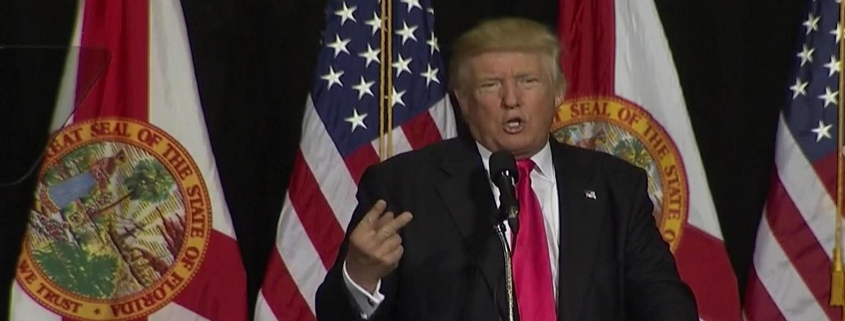

The king of real estate is set to rule the country, but what will a Donald Trump presidency mean for local real estate, one of South Florida’s biggest industries?

The Miami Herald wanted to gauge response from Realtors, developers, economists, bankers and lawyers about possible impacts of the election, both in the short and long term.

The Miami Herald asked: Will a new president — especially a political unknown like Trump — mean uncertainty for Miami real estate? What will the election’s impact be on sales and developer activity? They also wanted to know their views on whether Latin American investors would hesitate to invest in President Trump’s America after his strong anti-immigration stance. Will his election depress demand from Latin American buyers?

Overall, those who responded are mostly bullish, as you might expect from business people who depend on optimism and consumer confidence for sales. The Miami Herald selected a representative sampling of the views expressed and excerpted comments they made, mostly via email. (Thanks to the team at Bendixen & Amandi, the Miami Herald partners on their annual Real Estate survey, which helped put out the word.)

Mekael Teshome, economist at PNC Financial Services Group

Trump’s policies on immigration and trade could have the greatest effect on the South Florida real estate market, Teshome said.

“The president in a sense is using a blunt instrument where you’re dealing with the whole country. Real estate is an industry where it’s very localized. It would be hard for a President Trump to craft a policy that affects the real estate market in South Florida.”

Since the early 2000s, the local real estate industry has relied heavily on foreign investors. But their numbers have thinned because of a strong dollar and weak foreign economies. If Trump’s proposed policies result in higher tariffs, friction over trade and lower confidence in the United States as a stable haven for flight capital, that could scare away foreign investors, Teshome said. “Fewer foreign buyers would weaken demand.”

Jeff Morr, broker with Douglas Elliman, chair of Miami Master Brokers Forum

“I think people are just happy that the drawn out, vitriolic election process is over. Interest rates are low, the economy is solid and many prices have adjusted. The timing couldn’t be better for buying in Miami.” Longer term, he said: “I expect continued improvement barring any major catastrophes.”

Morr’s business is about half foreign, half domestic; his domestic business has grown because of the U.S. housing market recovery and a strong dollar.

Will Latin Americans continue to invest in Miami real estate? “The U.S. is still the U.S. — a safe haven for people from around the globe. Miami is the unofficial capital of Latin America and will continue to be the beneficiary of Latin American money.”

Jorge Pérez, CEO, Related Group

Pérez recently returned from a sales trip to Mexico and said the biggest fear of potential buyers for real estate is the possible visa status changes that could take place with Trump as president.

“We had to reassure our clients that in our opinion there will be no increased restrictions on visas or ownership requirements for foreign buyers. Trump is a businessman and understands the importance of foreign buyers. We have done four condominium towers with him in Florida, and he was part of the presentations to Latin Americans. … I believe that, if anything, he will try to promote this investment to help our economy grow.

“A very large percentage of our buyers are from South America and also from Europe. They invest not only because they love Miami’s lifestyle but also because it is the most secure country in which to invest. Uncertainty is a big deterrent to investment, and I hope that no policies are developed which in any way affect our standing as the most secure country in which to invest. I am also hoping that, after clear and unbiased reflection, Mr. Trump realizes that trade will lead to greater growth and employment in America, which is the cornerstone of his campaign.”

Avra Jain, real estate developer and investor

“Overall, Trump will have a positive effect on the real estate industry. People may pause for a week or two while they digest, but I expect the market to resume its positive course.”

Over the next 12 months, “given he is heavily invested in the real estate space, I would expect him to protect favorable real estate tax laws currently in place and will probably try to create more incentives to encourage investment/development. “Favorable policies will be good for everyone, but the personal tax incentives from the income and capital gains would benefit U.S./resident buyers more.”

Her personal concern: Supreme Court justice appointments and how that will affect her daughter’s generation.

Masoud Shojaee, president and chairman of Shoma Group

“We have seen so much unpredictability in the course of this election; we are dealing with a very unpredictable person. That will destabilize our dollar in the short term, which will create opportunities for foreign investors. …The message we are hearing from the new administration is that more jobs will be created, more infrastructures and growing of the economy. If this is truly the case, it will have a positive impact to our market. No matter what the rhetoric was prior to the election, the new administration will focus on reality and hopefully on the positive path this country needed badly.”

Marcelo Tenenbaum, co-principal of Blue Road, a Miami developer of residential, hospitality and commercial projects

As to the short-term impact of a Trump presidency on Miami real estate, as well as the impact one year out: “We don’t see any change in that trend. Miami has been a magnet for investors for more than 30 years, regardless of different presidents, political moods and parties — they look at the long term. … As the electoral campaign defuses, people will go back to business as usual. Trump talked about a tax cut, which might help to increase profit for investors. That is music to their ears.”

On Latin American investors in particular, he said, “Investors are pragmatic. They look at numbers and returns; they don’t look at political correctness, values, etc. If Trump reduces capital gains, income-tax rates and eliminates the estate tax (which is huge for foreign investors), they will keep investing in South Florida.”

Jack McCabe, a South Florida real estate analyst

The country was likely heading into a recession in 2017 no matter who was elected, but the uncertainty of a Trump presidency will accelerate it, McCabe said.

In South Florida, the implications of a Trump presidency will likely be most hard-felt among foreign buyers, who make up about 60 percent of South Florida real estate sales, he said, because of Trump’s disparaging remarks against Hispanics, Muslims and other minority groups.

“Without a doubt, Mexican buyers that have been a growing segment; I think many will find it difficult to invest.” The threat is particularly badly timed now, when foreign investment has eased due to recessions in other countries and a strong U.S. dollar.

Issues have arisen closer to home, too. Luxury real estate, which is largely bolstered by foreign investors, has been suffering from drops in resales and increasing supply. The uncertainty of Trump’s presidency will likely raise more questions for investors. In the past several months, several developers have put plans on hold due to the slowdown in the market, McCabe said.

“There is a tremendous amount of concern from different countries about how his presidency is going to affect global economics. We are headed for a very volatile period in the future, especially in the luxury real estate section.”

Marc Shuster, partner at Berger Singerman

“Generally speaking, I don’t see a connection to any president and his/her election on the one hand, and Miami real estate functionality, on the other. I think if anything we might see some pullback by U.S. investors in the short term who are concerned about yield over the next year or so.

“Conversely, the long-term tailwinds that the U.S. is positioned to inherit or even seize makes for a very rosy picture for Miami real estate in the long run. It is a premier destination, and a low-interest-rate environment creates a long-term play for prosperity.

“It seems dubious to me that his campaign speeches will be easily put into government, [with] the executive branch being checked by the Legislature and judicial. And I think, given the rest of the world has such strong economic dislocations, Miami will continue to be one bright spot on the world stage, almost out of necessity when looking at the entire world and desirous of achieving yield in cash-flowing assets. The weather, lack of state income tax, population growth, low-interest-rate environment will help.”

Jay Parker, CEO, Florida Brokerage, Douglas Elliman

Parker doesn’t expect a major impact this year.

“That said, I do believe the world in general has faced uncertainty by pausing on most major decisions, especially as we faced the end of a long and complicated election process. As has been seen in the stock market on the first day since the election, I expect that the world will find confidence in the fact that the U.S. is a strong and safe country to invest in. And as we see the country reunite, I think our real estate market will see a strong boost. I also expect that issues like Zika will subside, which will directly benefit Florida.

“Ultimately, I believe and expect Trump’s tax plan, banking regulations and overall effort to lower taxes will create more income, more spending power, which will lead to a housing industry boom. I expect we will see more impact as we move into the first and second quarters of 2017.”

In Florida, Douglas Elliman has seen slower velocity from foreign markets, but Parker believes that many such markets will resume their focus on the U.S., as he expects the security of investment and overall opportunity will increase under the Trump presidency. “I also believe that states like Florida will remain uniquely appealing due to our tax benefits and the continued maturity of our culture, educational institutions, hospitals and quality of life.”

Daniel de la Vega, president, One Sotheby’s International Realty

On a national macroeconomic level, most people will take a wait-and-see approach, de la Vega said. “From a local real estate level, I believe people just wanted to know the definite outcome. Now that they do, they feel more confident making their purchase. Donald started off on a good foot in his acceptance speech by saying he wants to bring America together, thanking everyone around him for his success and verbalizing his admiration for Hillary in a long hard-fought battle.

“Some of his fiscal policies and less regulation could lead to economic growth. Jobs created in states that are most competitive will lead to a healthy more stable U.S. Most foreign investors look for stability and a democratic place to put their money. Overall, this country always finds a way.

“2016 definitely shifted to a more domestic buyer. Financing has eased, and job and wage growth were on the rise. I believe this will continue if we make for a better America. This will not be about who our leader is, this will be about who we are as Americans. Like Deepak Chopra said: ‘Perhaps the future no longer depends on a single leader but on each of us who can quietly dedicate our life to light, love and healing.’”

Gil Dezer, Dezer Developments and Trump’s former business partner on several South Florida developments

“I think the overall economy will get a boost as consumer confidence grows due to the results of this election. Unfortunately, I’m sold out of Trump units in my six buildings, but I’m sure my clients will enjoy a nice bump in value. … I presume that a year from now is when we will really start to see the positive economic impacts of Mr. Trump’s presidency.”

Will Latin American investors in particular continue to choose to buy in Miami because the U.S. is a stable political and economic environment? “I think you answered your own question here. Latin American INVESTORS are doing just that. They are investing. There is a small fraction of them that actually leave their businesses and families behind to move here. I don’t believe there will be any changes to tourism policies or tourist visas. Latin Americans looking to emigrate to the U.S.A. will most likely go the EB-5 route. That is a completely separate transaction from a real estate purchase.”

Peggy Fucci, CEO, One World Properties

“I think our buyers will continue to see Miami as a safe haven — the U.S. continues to provide that image regardless of who the president is. The situation in all the markets that continue to buy Miami, especially Brazil and Argentina, hasn’t changed. Miami is a great bet. We are talking about a city that is poised to be the Hong Kong of the West with all the characteristics necessary — diversity, financial institutions — and it’s centrally located to South America and Europe.

“Trump has real estate in his blood. He has already said he is interested in boosting home ownership. If he shows that during the upcoming year by continuing to keep interest rates low, our housing market will continue to grow. There is too much international turmoil not to continue to keep our rates down. We will also see the rise of the U.S. buyer.”

She said international markets represent about 60 percent of her companies’ sales among all its projects. “Latin America has always invested in Miami … In addition, Trump’s immigration policy has changed since he started campaigning; immigration reform would be a tough bill to push through, so it’s difficult to determine whether this will have any influence in the real estate market.”

Armando Codina, developer and executive chairman, Codina Partners

“We do not believe that a new president equates to an uncertain real estate environment here in Miami. The Miami real estate market will probably react much like the stock market reacted [after the election results were announced] — a pre-market drop and then a quick rebound.

“If Trump is successful at getting his proposed tax plan into effect, we believe it will have a positive impact on the economy in general. Real estate will benefit from lower capital gains, and businesses should benefit from lower corporate rates. “Elections in Latin America have a much greater impact on us. America will continue to be seen as a great safe haven.”

Craig Studnicky, broker and principal of ISG World

Trump’s lack of experience in public affairs has international buyers and real estate developers concerned, Studnicky said, but Trump is a real estate developer — it’s in his blood.

“There are many people in Miami and abroad that are hoping Donald Trump will use his power as president to influence policies that are favorable for the real estate industry and build a healthy real estate economy. Time will tell. The real question is, in a year from now, will Donald Trump be perceived as a strong leader for the country and will his presidency be perceived as a benefit by the world? Domestically, he/it may be. It’s very unpredictable at the moment.”

Art Falcone, co-founder and managing principal of Encore Capital Management

Like traders in the stock market, real estate buyers may react to gyrations in the market and become skittish, Falcone said. “But as to developers, if you are not thinking long term, you should not be in this business. You can’t invest hundreds of millions of dollars into projects and overreact to short-term market changes.

“We were on the phone with some partners from China [Nov. 9], and there was certainly no overreaction about changing their long-term thinking about Miami. If Trump does half of the economic stimulus policies he has mentioned, versus things the media has hyperbolized as being hurtful to the economy, we would be in good shape. He’s certainly not going to eliminate trade altogether.

“With EB-5 projects, you could see a big push to file new applications because of the uncertainty of what the new administration might do with that program. There could be some very positive long-term benefits here if Trump and the policymakers are successful with the infrastructure investments they hope to facilitate. “In general, consumers don’t cause recessions — policymakers do. We have to keep a careful eye on what policymakers will do in the first year of the administration.”

Chris Zoller, broker at EWM Realty International

After an election year of uncertainty, Trump’s presidency ushers in an era of certainty, Zoller said. “Now we know what we have, but don’t forget one important thing: What we have is a system that works so well, that is still the strongest democracy on the planet, is still creating the safest place to be investing in real estate.”

Zoller expects the next few years to be prosperous, largely driven by economics, not politics. “In my experience, the president in the White House has much less to do with economics than the business community or the Treasury or the Federal Reserve System or Wall Street.”

Experts have worried that Latin American investors, who are major players in South Florida’s real estate industry, would be scared away by Trump’s anti-immigration stance. Zoller disagrees. “I don’t think every foreigner is looking to come here to live,” he said. “And I don’t think there is a more attractive place for them to make an investment [than Miami].”

Andrés Asion, master broker, founder/broker of Miami Real Estate Group

Asion was in Mexico for a poorly attended real estate expo that started the day after the U.S. election. While the peso was tumbling and the country seemed to be in shock about the news, Asion believes that will be temporary.

“Many Mexicans I spoke to feel that Trump is looking out for the best interest of the American people first and they understand that. [They] also feel that after the initial state of shock, Mexicans will continue to invest in the United States because other areas like Europe are too far and South America does not offer the security of the United States. … They feel people will always want to invest in a country that is doing well, so if Trump’s policies will make the U.S. economy strong, it will in turn make everyone else want to invest into it, regardless… The people I spoke to also understand that Trump wants to have a hard stance on immigration.

“In the short term, the hold from many Latin Americans in ‘wait-and-see mode’ will cause sellers in Miami to possibly lower prices in order to move units quicker as the South Americans slow their buying power for approximately the next six months.”

James Shindell, attorney and chair of Bilzin Sumberg’s real estate group

“On the commercial side, Miami will continue to be an attractive destination for Latin American capital. It is still an exciting gateway market on an upward trajectory. It is still Spanish-speaking. It is still safe. The rule of law still applies. Alternative investment choices haven’t suddenly lost their flaws. If that’s not enough, the president-elect is a real estate developer.”

Dan Kodsi, developer and CEO of Paramount Ventures

Kodsi said a Trump presidency may create some short-term uncertainty in the Miami real estate market, which may weaken the dollar over the next 60 days and send a buy signal to Miami’s largest market, South America, as a good time to buy.

As Trump begins to build his cabinet with fiscally conservative Republicans combined with private sector ex-CEOs who wouldn’t ordinarily get involved in the public sector, it will create a new confidence in our economy, Kodsi said. “While our largest market the Latin Americans may be offended by Mr. Trump’s rhetoric, they will make investment decisions based on the strength of our economy, not his personality. Continuing the reckless spending of past administrations will continue to weaken us over time and would have created an unforeseen long-term issue.”

About 90 percent of Kodsi’s business is from foreigners — about the same as a year ago, he said. “Most of the Latin Americans that invest in Miami do not come to the country illegally. His anti-immigration stance is against illegal immigration, not overall immigration to the U.S. The type of buyers that invest in Miami real estate are the immigrants that a Trump administration will most likely incentivize to come live and invest in the U.S.”

Mike Pappas, Realtor, CEO and president of the Keyes Company

The market likes clarity and consistency. There may be a slight pause until the market understands his economic and immigration plan. Longer term, “If Trump implements a pro-business strategy, then that will lift sales and prices.”

Thirty percent of Keyes’ Miami-Dade market is from foreign buyers. “With the dollar strengthening and turmoil in Venezuela, along with political and economic issues in Brazil, we have seen a slight decrease this past year. We are seeing a rising interest now from Asia, as well as a strengthening of the northeast domestic market toward South Florida. For the long term, there’s no effect. In fact, it may actually be positive. As for the short term, they may sit on the sideline until they are comfortable with the new policies.”

Ezra Katz, real estate investor, CEO of Aztec Group

“Donald Trump is a businessman and developer by trade, so I believe his presidency will positively impact our economy — and by extension, real estate development, finance and sales. I think his administration will create jobs, which will stimulate consumer spending, and I believe he will be pro-business. By eliminating many of the bureaucratic regulations that are hurting U.S. companies, we will encourage entrepreneurship and entice companies to relocate to gateway markets like South Florida. The real wild card is whether President-elect Trump will reach across the aisle to work with members of both parties in Congress. If he makes bipartisanship a priority, then the U.S. economy is destined for significant growth.

“The U.S. will be a significantly better-managed country under President Trump, particularly when compared with nations in Latin America and Europe. As people overseas begin to see the U.S. economy thriving, it’s only natural that they will want to join in on the growth and profit themselves by opening businesses here and investing here — as they should. The vast majority of inbound investors in South Florida are migrating and doing business here legally, so President-elect Trump’s stance on immigration is unlikely to have a measurable effect on our regional real estate economy.”

Karen Elmir, broker, CEO of the Elmir Group

Elmir believes short-term impact will be minimal. “The long-term projections relative to Miami real estate are positive due to the economic policies of President-elect Donald Trump — lowering of tax rates for individuals and corporations, and the reduction of governmental regulations. These should result in an increase in the GDP from the current lethargic figure of 1 to 1 1/2 percent to a robust projected increase of 2 1/2 to 4 percent GDP projected for mid-2017 through mid-2018. A commensurate increase in property values in part due to the increase in GDP and in part due to these policies will result in a slight increase in the inflation rate, which should create upward pressure on residential prices.”

Foreign nationals find investment in Miami real estate attractive because of proximity to South and Central America and the stability of the United States’ political and economic environment, she said. “The immigration policy should have minimal impact on buyers of luxury real estate in Miami.”

Calixto Garcia-Velez, executive vice president of FirstBank Florida

“Sales and developer activity are affected by economic drivers, not necessarily political changes. For example, the Federal Reserve has the potential to have a more effective impact on real estate, as any increase or decrease in interest rates can materially affect someone’s ability to pay a mortgage/loan. Although the new president cannot directly influence the Fed, the movement we’ve seen across America and the new administration’s platform could influence the Fed’s decision-making process moving forward.

“It is premature to predict long-term activity as a result of the election. In any event, it is important to note that change in political arena does not necessarily mean change in the real estate market. More significant drivers are what occurs in the world markets and the countries that directly contribute to our real estate activity. For example, Latin America’s economics and political landscape may have more of an effect than short- or long-term election results.

“Regardless of who is president of the United States, Miami has been, and will continue to be, a safe investment and beacon of strength and stability for Latin American investors.”

Ron Shuffield, Realtor, president and CEO of EWM Realty International

Shuffield does not think it means uncertainty for the market because Trump is such a highly recognized entity within Miami’s real estate community. “A president-elect who has frequently stated that one of his main goals in office is to address overregulation by the government would have an immediate positive impact on the market.

“I see it as all the more positive in the long run. While much of the luxury market is driven by cash or mostly cash sales, securing a mortgage, especially at the entry level, has become incredibly cumbersome. The overly stringent credit limits that came to pass as a reaction to the financial issues from the recession have had a very negative influence on specifically, the entry level market. His working to eliminate unnecessary barriers will certainly help keep the market moving forward at a viable growth pace.”

Shuffield also doesn’t see negative fallout in the Latin American market. “The person who is purchasing in South Florida is in the U.S. legally, and they certainly have means. Trump has always said that he has no issue with people who are in the U.S. legally. Will the Latin American buyer be psychologically affected and hence not purchase? For the most part, I really do not think so because we are already seeing a softening of that stance from even 60 days ago. I believe Trump’s pro-business, pro-real estate stance will compensate for any negative feelings they may have.”

Alex Zylberglait, broker and senior vice president of investments with Marcus & Millichap

In the short term, uncertainty created by a new administration will most likely mean a pause among some investors until emotions settle down. But Zylberglait doesn’t project a slowdown in deals. “Miami real estate deals in South Florida and especially Miami are, in big part, fueled by foreign capital. Except for Mexico, the impact of the Trump elections hasn’t reflected negatively on the value of their currency against the dollar. On the contrary, from the yen to the euro, currencies around the world gained strength, making U.S. real estate more affordable. Also, many real estate investors feel comfortable having a real estate person calling the shots in the White House.

“Having said that, every new administration brings uncertainty to the market so we may see a rush to close deals before Jan. 20 to take advantage of current rules on the books to play it safe. I would not be surprised if the uncertainty in the stock market will re-direct capital to the real estate market in search for a better return.”

Longer term, it will all depend on how the credit markets respond to the new administration, Zylberglait said. “If banks trust Trump’s ability to govern and support its agenda in terms of lending regulations, lenders will feel comfortable refinancing deals and making acquisition and construction loans. Otherwise, it will negatively impact the future of deals because most domestic investors need financing to close on a deal and developers to finance new construction. Since many foreign investors buy cash, they will have the flexibility to buy assets even when the U.S. credit markets put more restrictions on lending. Miami benefits from cash-buyers from across the globe so a tighter lending environment will have less of an impact in Miami than in other cities.”

Zylberglait doesn’t see a slowdown in foreign investment on commercial real estate in the $1 million to $20 million range. “Having said that, if the Trump administration develops an anti-immigration stance, it will hurt deals. Investors are people and they go where they feel welcome. … It is important to see how governments across LatAm will react to Trump’s unexpected victory.”

Edward W. Easton, chairman and CEO of the Easton Group based in Doral

“In my opinion, President Donald Trump will not be harmful to Miami real estate. Because he understands real estate, I’m of the belief that he’ll be pro-growth between South and Central America, and North America — and that will be to our benefit, if in fact it happens. Same for long-term activity: It will take time, but in my opinion, it will be neutral or positive.”

Easton believes there will be a waiting period where people watch and see what kind of people Trump surrounds himself with. “I’m hopeful he will be a pro-business president and will cut back on the regulations that I believe are harming our economy.”

Foreign sales are down, but mainly because of currency, not because who the president is, he said. “What will be helpful is if the Trump presidency will be less regulatory than the Obama presidency. Regulations, especially around the Dodd Frank Act, have caused some worry for potential investors from South and Central America. That basically puts the burden on the investor to supply a lot of the documentation to the government about what they’re doing. And that’s not something investors want to have happen. So, maybe by Trump eliminating a lot of the regulations, that will be very positive for investment in the United States by foreigners.”

Regarding Latin American investment, “I believe it will be a net positive. Their fears of investing are coming from what’s going on in their own countries, more than the fears of what’s going on politically in our country. Real estate is a protective asset for them, and I don’t think that reality changes. They feel safe putting money in America and that will continue. Regulatory behavior will be helpful for that.”

Aaron Drucker, managing broker in Miami for national real estate brokerage Redfin

Inventory levels and economics will drive consumer decision-making, not election results. Any uncertainty will be short term as Trump lays out more concrete plans for how he’ll help the housing market, Drucker said.

Some wealthy sellers may delay listing their homes this year, hoping to get a more favorable death tax rate, he said. Trump’s proposed tax plan does include repealing the “Death Tax.” “I don’t believe developers will make any rash decisions or change any current promotions they are advertising. For projects currently on hold, it’s likely some developers will revisit coming to market if they believe GDP growth will improve under a Trump presidency and a Republican-led congress.”

Long term, if Trump can execute his tax plan, business and personal taxes will be cut from current levels, Drucker said. Finance regulations implemented under Dodd-Frank and the CFPB could be repealed or replaced with guidelines that are more business-friendly.

“One of the biggest impacts Trump can have to the housing market long term is a refocus on FHA loans. Those are the federal government’s strongest tools for increasing home ownership and expanding access to housing for low-to-middle income and minority Americans, but the mortgage insurance premium for the life of the home loan under FHA can be a deterrent for some borrowers. If Trump can remove that premium, we could see increased access to home ownership and sales volume in the market.”

Trump can also relax some of the scrutiny appraisers must give to the “condition” of the home required when a veteran obtains a VA loan, Drucker said. “When veterans are trying to buy a home with a VA loan and get into multiple-offer situations, it can be hard to compete with other buyers bringing conventional loans or cash to the table. Trump has talked a lot in the campaign about the importance of taking care of our veterans, so we’ll see if he incorporates their housing needs into his plan.”

Jill Hertzberg and Jill Eber, “The Jills” at Coldwell Banker, master brokers

Uncertainty can rattle the stock market, which impacts the high-end luxury market, The Jills said. Election night was difficult for the market, but it rebounded the next day.

Longer term, “It’s hard to have a crystal ball, but the Miami market will really depend on the growth of the economy in the next year, both here in the U.S. and economies around the globe. The world is so interconnected, and we are very dependent on what happens in our feeder markets. We are a primary as well as a second- and third-home market, and we are very attractive [for] our favorable taxation [and] reasonable pricing compared to the Northeast U.S., California, Europe and Brazil, and [the U.S. is] a safe country for capital flight.”

South Americans will continue to invest in Miami, the Jills believe. “They have been coming for years and years, they have relatives and friends here, and they are very comfortable here.”

Mark Meland, a partner at Meland, Russin and Budwick

While markets don’t like uncertainty, the transactions scheduled to close before the end of the year likely took political risks into consideration, Meland said. “So, in the short term, we do not see much impact [on] the markets. Certainly, interest rate volatility is more impactful in the short run. In the long term, a Republican president with a Republican House and Senate should provide for similar, or favorable, tax treatment for real estate transactions.”

The maturity and stability of the market and the U.S. dollar are more important factors than immigration policy, he said. “While some foreign buyers may be investing for immigration purposes, i.e. EB-5 investments, most are investing in the U.S. market for the stability of the market, as a hedge against currency fluctuations/devaluations and inflation in native countries. The devaluation of Latin American currencies to the dollar (i.e. Mexico) could have potentially negative effects on the real estate market as U.S. real estate assets will be more expensive for these foreigners.”

Paul Shelowitz and Ira Teicher, real estate attorneys at Stroock, Stroock & Lavan

These attorneys think that in the short term, Trump’s victory will temporarily chill sales activity, given how overheated the real estate market is right now. As to developer activity, there will be little or no discernible impact given the long lead time associated with project development, they said.

“Our clients tell us that uncertainty relative to a Trump presidency is expected to create buying opportunities. Of course, with that comes additional risk. Our clients are already acting on the news and putting out feelers for jittery institutions and the like. Our clients have also noted that a positive/negative start to Trump’s administration might bring added/reduced value to properties located in the vicinity of Trump branded assets. The latter point of course remains to be seen.”

They believe Latin American investors will perceive the same opportunities that their domestic clients have noted. “Our experience dictates that shrewd investors — here or abroad — are able to divorce their own political views from their investment decisions. We don’t believe that Trump’s anti-immigration stance will materially impact that analysis.”

Ken Krasnow, executive managing director for the South Florida region, Colliers International

The lack of certainty and unpredictable nature of any election affects investor confidence, Krasnow said, but market volatility was short-lived, and, ultimately investors found opportunity.

“While uncertainty levels remain high, we expect the Fed to delay raising interest rates this year, and investors may push investment decisions into Q1 until they understand what a Trump presidency means for them. … Miami is already recognized as a safe haven for investors, and Trump’s promise to lower taxes and reduce capital-gains rates could spur additional investment here. An area to watch would be the industrial market: Trump’s plans to renegotiate trade agreements may pose a level of uncertainty for Miami. Global trade and job growth have been a catalyst for the growth of Miami’s industrial market.”

Liza Mendez, Realtor

“Some portions of the market have been at a standstill, waiting the results. Now that we know the direction, the marketplace will start to make decisions on what is best.” But Mendez is most optimistic about “getting our government to actually work on the issues and provide solutions rather than gridlock.”

Source: Miami Herald

Aside from Brickell City Centre, which has two more planned phases yet to start, the SAP has also led to the lauded, near-total redevelopment of the formerly dormant Miami Design District. The rebirth of the district, about 60 percent complete, has meant new, street-friendly retail buildings and a pedestrian promenade connecting two large public plazas.

Aside from Brickell City Centre, which has two more planned phases yet to start, the SAP has also led to the lauded, near-total redevelopment of the formerly dormant Miami Design District. The rebirth of the district, about 60 percent complete, has meant new, street-friendly retail buildings and a pedestrian promenade connecting two large public plazas.