The metamorphosis that’s already taken Wynwood’s industrial district from urban blight to urban paragon in record time seems poised for a dose of development Muscle Milk that could pump up the scale of construction along a broad, mostly vacant swath of the neighborhood to new, and somewhat controversial, heights.

The two biggest players in Wynwood’s snowballing transformation, at odds for months over a massive redevelopment proposal that some fear could overwhelm the human scale and funky vibe that define the district, have reached an agreement that softens its impact on the neighborhood fabric of spiffed-up warehouses, and likely clears the way for its preliminary approval by the Miami City Commission.

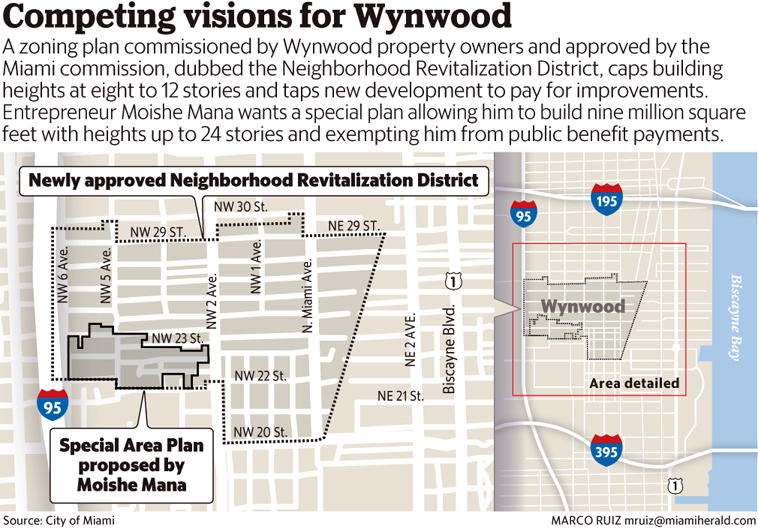

That would mean that Wynwood’s largest landowner — moving-company and arts entrepreneur Moishe Mana — can move ahead with an ambitious 30-year blueprint for what amounts to a miniature city containing nine million square feet of space on some 24 acres of mostly vacant land stretching from the neighborhood’s main street, Northwest Second Avenue, to its western edge at Interstate 95. The contemplated Mana district, centered around a green public central square, or “commons,” that would cut diagonally through the development, is aimed at luring tech companies, commercial trade and arts and cultural institutions to Wynwood.

The board of Wynwood’s Business Improvement District, a city-chartered agency that represents most property owners in the rest of the former industrial zone, voted Wednesday to support the Mana Special Area Plan after winning a series of concessions aimed at making sure the developer’s new buildings mesh with the surrounding fabric of simple industrial buildings, many of which have been transformed into art galleries, offices, shops and dining and drinking spots.

“There was a lot of reasonable anxiety that you would have this district-within-the district that would be out of scale and out of character with the area,” said Albert Garcia, a member of the BID’s board and its planning committee, which negotiated the deal with Mana. “Over the last six months we’ve made a lot of progress in dialing that back so that it doesn’t suck the life out of Wynwood, which is the nightmare scenario. It’s a much better plan. I believe Mr. Mana understands our vision and it’s now a shared vision. We like to do things on a community basis and seek consensus. That’s the DNA of Wynwood. Wynwood is a special place. It’s not a race to the sky.”

Mana’s architect and planner, Bernard Zyscovich, said the developer and his team are happy with the revised plan. Though it’s now scheduled for the first of two commission votes on Thursday, Zyscovich said Mana will likely ask for a two-week postponement to address issues brought up by residents of neighboring Overtown and Commissioner Keon Hardemon, whose district includes both neighborhoods. Those concerns include how the new development would affect adjacent residential areas in Overtown as well as the availability of jobs for residents.

“It’s all positive,” Zyscovich said. “I think we have a great plan, a plan that’s going to create a whole neighborhood that’s exciting and beneficial to our neighbors.”

The BID also had to relent on some issues. Mana would not budge on plan provisions that would allow him to build residential towers of up to 24 stories. But Mana’s team agreed to push those off Second Avenue to the western portions of his property along Northwest Fifth Avenue and I-95, and to conform to current, lower zoning where new buildings would face the existing neighborhood.

Mana’s proposal, unveiled at the end of 2015, riled BID leaders and neighboring property owners. After more than a year of planning, they had just won city approval for special zoning rules designed to control development by increasing allowed heights in most of the old Wynwood industrial district but capping them at eight or 12 stories, depending on location. The goal of the Neighborhood Revitalization District, as the new zoning plan was dubbed, is to foster development of relatively inexpensive housing and new office and retail space while preserving the neighborhood’s modest scale and pedestrian-friendly ambiance.

To take advantage of the increase, developers must pay into a special fund to help finance parking garages, affordable housing, creation of public green space and landscaping and improvement of streets and sidewalks, but Mana wanted to be exempted from the fees. He has now also agreed to participate in funding the programs.

Other changes to Mana’s initial plan aim to ensure his district is closely connected with the surrounding neighborhood. The rules would now require “active uses” like shops and restaurants at sidewalk level along principal facades and pedestrian passageways to break up large structures and encourage walking.

“If you’re a pedestrian crossing the street or you are driving down the street, it’s going to feel continuous and harmonious,” Garcia said. “We didn’t want those jarring transitions where you might have eight-story buildings on one side of the street and 24 stories on the other.”

New rules also allow Mana to begin building his taller residential structures only after he has completed defined percentages of the promised commercial and cultural buildings and public amenities, including meeting space and the central commons. That’s to ensure that those elements, which BID leaders and other neighborhood supporters say are critical to Wynwood’s evolution and comprise the most significant pieces of the Mana plan, don’t get lost or left for last, they said.

“What will make Wynwood an interesting place in 10 years from now and 20 years from now is if that art school and the cultural institutions and tech set up permanent camp here,” said David Polinsky, a developer who is a BID board member and chair of the planning committee. “Not everybody’s happy with the scale [of the Mana plans]. But the board feels reasonable compromises were made. There are still lots of good things that can come out of the [project] if it’s executed well.”

Those good things, Zyscovich said, will include buildings with large, flexible floorplates that can accommodate everything from showrooms and meeting rooms to offices, art exhibition galleries and “maker spaces.” Mana is now working on a plan to create an international trade center on site to link buyers and suppliers of products in Asia and Latin America, he said. Mana also plans to replicate elements of his Mana Contemporary art center, a converted tobacco warehouse in Jersey City, New Jersey, that combines artist studios and exhibition galleries with services such as fine-art storage, transportation and conservation, Zyscovich said. The plan also includes hotels, but the potential residential buildings, Zyscovich stressed, are secondary.

“Our main idea is not to create more residential, which everyone is doing,” Zyscovich said. “We’re looking for a job creation strategy. Showrooms, office infrastructure, entrepreneurial spaces — all that is very much the idea.”

There are some unsettled matters. Mana, whose holdings are centered around the former Wynwood Free Trade Zone complex, which he purchased in 2010, has been using the facility and adjacent vacant land for large special events under a temporary permit, including a reggae performance that recently drew a reported 60,000 people.

BID leaders want those events curbed because they say they’re disruptive and detract from Wynwood’s particular ethos. Mana has in principle agreed to abide by normal city rules for such events. They also want Mana to support a proposed expansion of the boundaries of the BID — a special taxing district that levies a fee on property owners to support special services like security and trash cleanup.

Some Mana properties now sit outside the BID boundary, but the expansion would mean all of Mana’s holdings would be subject to the levy. Mana — whose failure to vote on any of his properties contributed to a defeat last year of a previous effort to expand the BID — has agreed to support the expansion. But he has not committed to paying the additional levy. If the city commission approves Mana’s development plan on first reading, the BID agreed it would negotiate the terms of his participation before the second reading.

The BID board made it clear last week that they would rescind support for Mana’s plan if he doesn’t follow through on his promise to support the expansion. Because the plan is conceptual and doesn’t bind Mana to building as promised, there is still substantial concern in Wynwood over the proposal and its potential impact on the neighborhood renaissance, Garcia said. But if Mana does follow through on his promises, he added, Wynwood stands to benefit significantly.

“On the plus side, if it’s developed as planned and does bring the economic stimulation it promises, it’s a win for Wynwood and for Miami,” Garcia said.

Source: Miami Herald