A new strategic vision, competitive pricing and a less hectic lifestyle are three reasons North Miami Beach is emerging as an attractive location for new residential and commercial investment.

Both the scenic Biscayne Boulevard corridor and the 163rd Street commercial district are in the early stages of an exciting transformation that will bring many positive benefits and developments to the city.

Led by Mayor George Vallejo, the city of North Miami Beach adopted a strategic plan in September that sets guidelines for real-estate development, design and zoning for the next 15 years. The “visioning” framework, which was guided by two consulting firms, encourages new mixed-use projects and high-end residential towers in appropriate locations. It also includes funds for a comprehensive parks master plan, which will make the city an even more appealing place to live.

Led by Mayor George Vallejo, the city of North Miami Beach adopted a strategic plan in September that sets guidelines for real-estate development, design and zoning for the next 15 years. The “visioning” framework, which was guided by two consulting firms, encourages new mixed-use projects and high-end residential towers in appropriate locations. It also includes funds for a comprehensive parks master plan, which will make the city an even more appealing place to live.

Already, a new wave of commercial development is under way, including plans for new high-end restaurants and a hotel along West Dixie Highway south of the roadway congestion in Aventura. Gil Dezer, president of Dezer Developers in Sunny Isles Beach, purchased the Intracoastal Mall for $63.5 million last year and plans to open a luxury iPic theater in the mall this summer.

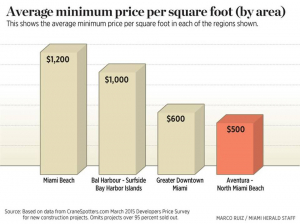

On the residential side, North Miami Beach is becoming a destination of choice for both domestic and international buyers seeking an alternative to higher-priced properties in more congested areas along the beach, in Aventura or in downtown Miami. Because the redevelopment of North Miami Beach is just in the early stages, pricing for luxury residences is more attractive than other markets that have already experienced a run-up in values.

For example, the sales prices for the second tower of Marina Palms Yacht Club & Residences, now under development on Biscayne Boulevard, averages $550 per square foot. To the north, a residence in a new Aventura building would be $850 per square foot, and the price for oceanfront units could be double or triple that rate.

Looking back at the last few decades, it’s clear that South Florida communities are at varying stages of the real-estate cycle. For instance, South Beach real estate was a bargain in the 1980s, before a wave of new hospitality, retail and residential investment created one of the world’s most popular (and expensive) urban resort markets.

Downtown languished until the early 2000s, when new residential and mixed-use developments exploded on the scene. After the recession, developers were quick to pick up unfinished projects and market them on an all-cash basis to affluent buyers from Latin America and Europe.

Meanwhile, North Miami Beach has remained a quiet, suburban city with about 40,000 residents and great recreational amenities, such as Greynolds Park and Oleta River State Park. In addition, the Biscayne Bay campus of Florida International University is conveniently located in nearby North Miami.

With its new strategic plan in place and a growing flow of commercial and residential real-estate investment, North Miami Beach is entering a new era, just as other Miami-Dade communities have evolved in the past.

Now the world is about to discover the new “hidden gem” in South Florida’s real-estate market. It’s an exciting time to participate in the transformation process, which will create a bright future for North Miami Beach and its residents.

Source: Miami Herald