An entrepreneur who’s bought a big chunk of downtown Miami while promising some mold-breaking surprises was apparently not kidding: He wants to build an eye-catching 49-story tower with apartments so small there’s no room for ovens in the tiny kitchens. And there’s no parking.

Actually, that last bit’s not quite right. There will be parking — for bicycles. Is Miami really ready for this?

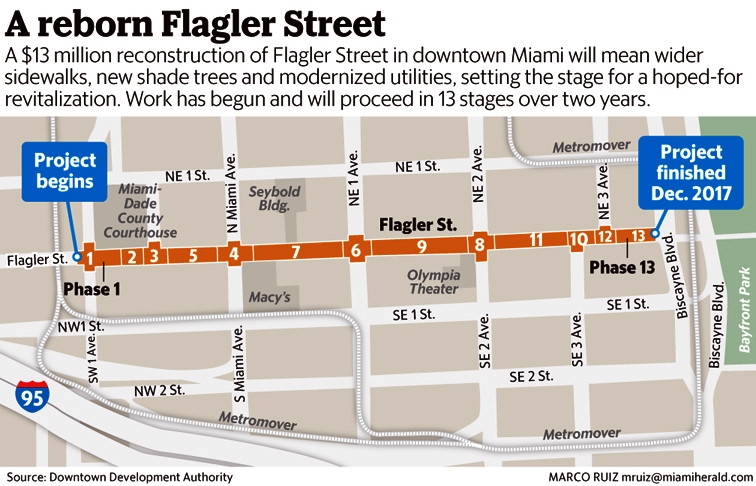

Moving-company and arts mogul Moishe Mana — who’s also building a mini-city on a large swath of Wynwood and has lately spent tens of millions to buy up property on and around downtown’s Flagler Street — certainly thinks so.

A rendering of developer Moishe Mana’s proposed “micro-living” apartment tower. (Zyscovich Architects)

He’s the first in Miami to formally propose putting up a building consisting entirely of what’s been dubbed “micro-units” — compact, hyper-efficient and affordable apartments meant for young singles who want to live in dense urban neighborhoods and get around primarily on foot and public transit. The plan, which Mana’s team says fully conforms with downtown zoning rules, will have its first and likely only public review before the city’s Urban Design Review Board on Monday

The blueprint calls for 328 apartments starting at 400 square feet, the minimum allowed by city code. The penthouse units top out at a relatively generous 600 square feet, but most will be 500 square feet and under, said the project’s architect, Bernard Zyscovich.

The blueprint calls for 328 apartments starting at 400 square feet, the minimum allowed by city code. The penthouse units top out at a relatively generous 600 square feet, but most will be 500 square feet and under, said the project’s architect, Bernard Zyscovich.

The apartments would be equipped with built-in furnishings, including beds and tables, that tilt, fold or slide into walls and cabinets, Zyscovich said. And the building, at 200 North Miami Ave., would be flush with amenities, including built-in superfast WiFi and fully equipped common kitchens and dining rooms for when residents want to entertain.

“It’s like living in a Transformer,” Zyscovich said. “The idea was, let’s make these apartments in the urban core, let’s make them small and let’s build in all the stuff that makes it desirable. We’re going for that authentic coolness that comes from being in the middle of everything. It’s for a particular type of person, probably Millenials but not exclusively so, who want to live an urban life and simplify their life, and not have all their money going to rent and furniture and maintaining a car.”

Rents, which have not been set, would be at market rates, but would be significantly lower than the norm downtown and in surrounding neighborhoods like Brickell — where high costs have some renters taking in roommates and doubling up in bedrooms — by virtue of the apartments’ small size. The substantial savings Mana will realize by not having to build costly structured parking will also help keep rents down, Zyscovich said.

A rendering of developer Moishe Mana’s proposed “micro-living” apartment tower. (Zyscovich Architects)

The project takes advantage of a zoning exemption that allows buildings close to transit stations in downtown Miami to dispense with parking. The building, on a sliver of land that Zyscovich said would make it hard to fit in a parking garage in any case, sits a short stroll from the Government Center Metrorail station, three Metromover stops and the station for the All Aboard Florida train service, now under construction.

There is lots to walk to nearby, including courthouses, government buildings and offices with tens of thousands of jobs, not to mention classes at Miami Dade College’s downtown campus two blocks away. The All Aboard station will have a food market, and Whole Foods and Publix stores can be reached by Metromover or city trolley.

Those who insist on having a car have options: The building site abuts a big city parking garage, and another public garage sits a couple of blocks away.

Two South Florida analysts predicted Mana will have no trouble renting out the building at a time where rents in Miami have risen much faster than salaries, creating a housing affordability crisis.

If Mana rents his apartments in the middle of the range for the area, or about $2.25 a square foot, that means someone could get into one of the 400-square-foot units for $900 a month, a relative bargain, while enjoying the privacy of his or her own space, noted Jack McCabe at McCabe Research in Broward County.

“They will fill it up,” McCabe said even as he expressed surprise at the apartments’ size and lack of fully equipped kitchens — though they will have cooktops. “Affordability is key right now. There is definitely demand for more-affordable rentals without a real kitchen in a cramped apartment that allows you to enjoy the lifestyle in downtown Miami.”

McCabe said the common kitchens, which Zyscovich said would have to be booked in advance, are a desirable feature for many people, and the compact units would not bother many of the South Americans and Europeans now flocking to the city who are used to living in smaller spaces than Americans.

The “micro-living” concept, which is catching on in other U.S. cities like Seattle, San Francisco and New York — the Big Apple’s first such building just opened in the Kip’s Bay neighborhood on the east side of Manhattan — can help solve not just the affordability problem but also relieve traffic congestion, said Suzanne Hollander, a broker and lawyer who teaches at Florida International University’s Hollo School of Real Estate.

“It’s very smart. It’s pioneering,” Hollander said. “Micro units are tiny solutions to big urban problems, and Miami is becoming a big urban city. It gives options to a lot of people who otherwise would not have them, so they can enjoy the urban living we are building.”

Micro-living buildings also carry other potential social benefits that could prove attractive not just to Millenials but also to retirees or business executives who need a pied-a-terre, she added.

“People sleep in a micro-unit. But, really, the whole building is their home,” Hollander said. “And the amenities here are amazing. What they’re trading is space for an A-plus location. This all encourages people to interact not just inside the building, but in the neighborhood, making everything more social.”

Another benefit, she said: Because the units are new and built to code, they are safer alternatives to the unregulated rooms in older homes or apartment houses that are often the only alternative for people on limited incomes.

Micro-units in New York and elsewhere are even smaller than Mana’s, with those in New York’s Carmel Place ranging from 260 to 360 square feet after the city waived its 400-square-foot minimum. That’s something some advocates are pushing to happen in Miami as well.

The no-parking alternative has a longer track record in Miami. Other developers have used the transit exemption to build no-parking residential towers downtown, including Related Group’s Loft buildings, but those units are for sale and tend to be larger. Units at Centro Miami, a high-rise condo tower now nearing completion, also without parking, range from 500 to over 1,111 square feet.

A new city zoning rule also allows for small buildings near transit routes to forgo parking. A small developer has broken ground on townhouse-like apartments without parking in East Little Havana.

Though Mana’s apartments will be small, the tower’s design aims to make a big impression, Zyscovich said. It looks like stacked blocks, with some sides on the west and south screened with a “veil” of metal mesh to shade them from the sun.

“It wants to say, I may filled with micro-units, but I’m cool,” the architect said.

Source: Miami Herald