In a metropolis where everything seems to change constantly, Coral Gables’ Miracle Mile has been a holdover — a last-century Main Street not far removed from the 1950s in spirit and urban form, complete with angled street parking, narrow sidewalks, under-nourished street trees and, until recently, a respectably unexciting mix of mom-and-pop shops, jewelers and more bridal shops than anyone could care to count.

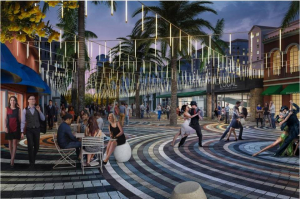

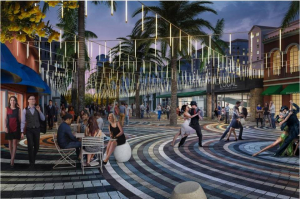

A rendering of a redesigned Miracle Mile streetscape showing wider sidewalks, a new paving pattern recalling the sky, parallel parking instead of angled parking, and new trees. (Credit: Cooper, Robertson & Partners – City of Coral Gables)

But it’s all been looking decidedly tired of late. Even as a sprinkling of stylish new restaurants and boutiques begins to brighten up the Mile, its sidewalks are stained and buckling and accommodate but a few cramped cafe tables. Raw dirt fills the open street-tree planters. Corner wood benches are splintering. Automobiles speed through noisily, subjecting pedestrians to long, discomfiting waits to cross the street.

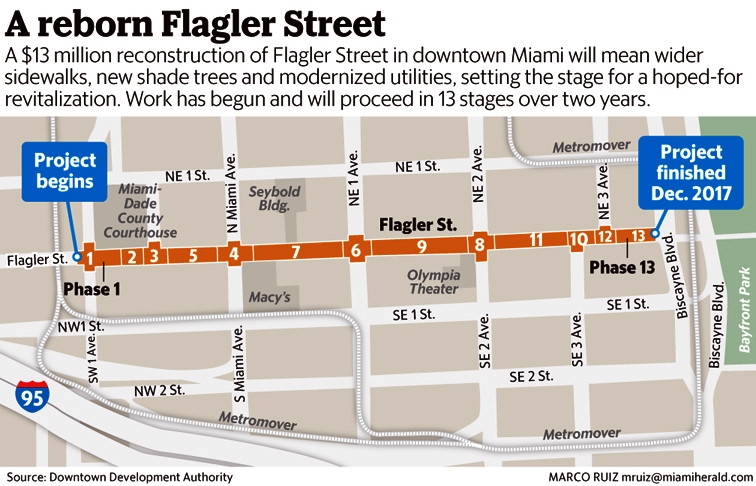

Not, merchants and city and civic leaders say, what you’d expect from one of South Florida’s signature drags. And so Miracle Mile will become the latest to undergo a wholesale makeover designed to secure its viability by enhancing what planners call the public realm, much like the retrofits that have re-energized its South Florida competitors on Ocean Drive and Lincoln Road Mall in Miami Beach, South Miami’s Sunset Drive and Worth Avenue in Palm Beach. Even Flagler Street in downtown Miami is now undergoing its own hopeful pedestrian-friendly facelift.

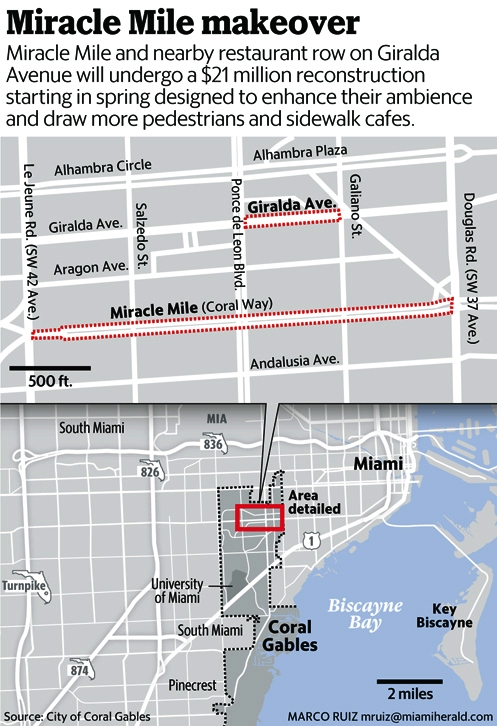

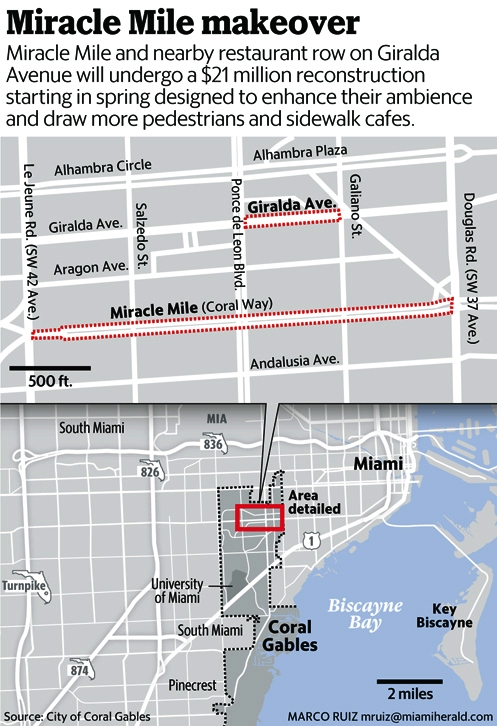

A rendering shows restaurant row on Giralda Avenue rebuilt without curbs and with trees in the middle of the street, in the fashion of a European plaza. Bright street pavers describe concentric circles resembling ripples in a puddle, while LED lights overhead are designed to recall falling raindrops. (Credit: Cooper, Robertson & Partners – City of Coral Gables)

The $21 million Gables streetscape project, which got a green light from the city commission last month and should get under way by spring, starts with dramatically wider sidewalks, covered in a multi-hued granite meant to resemble a cloud-dabbed South Florida sky. Curbs will be removed and the street edge defined by low stone bollards and a lush, densely layered tree canopy. Garden-like spots for lingering will occupy every corner and mid-block street crossing.

To expand sidewalk width from 15 feet to 23 feet, street parking will shift from angled to parallel parking. To slow down motorists and move them farther from the sidewalk, one of two traffic lanes in each direction will be slightly narrowed. The goal, city officials and planners say, is a welcoming ambience for people on foot, something struggling business owners on the Mile wish they’d see lots more of.

The plan, devised by one of the country’s top urban-design firms, provides what people look for in a Main Street today, they say: Ample space for strolling, shopping and sidewalk dining, all of it wrapped in a sexily distinctive look that will shine equally in the pages of Architectural Digest or on Instagram.

“Our task was to create a street unlike any other in the world, a street that says ‘Coral Gables,’” said Earl Jackson IV, the partner in charge of the plan for Cooper, Robertson & Partners of New York, during a public meeting last year. “It can be one of the great streets in the world if we get it right.”

The project will extend two blocks away to Giralda Avenue, the faded restaurant row that will undergo a parallel transformation. That single long block will be remade as a shared space between cars and pedestrians, with trees in the middle of the street to slow motorists and a curbless design to give Giralda the feel of a European plaza. Colorful granite pavers set in concentric circles, like ripples in a puddle, will extend all the way across Giralda, from storefront to storefront. Overhead, LED lights designed to resemble falling raindrops will hang from wires.

A thick scrim of trees will create a formal entrance at either end of Giralda. Removable bollards, meanwhile, will allow the street to be readily shut to autos for events like the popular, seasonal Giralda under the Stars, during which restaurants fill the block for a night with tables, music and dancing.

The project and its poetically fanciful design features have been enthusiastically embraced by a majority of the city council and most Miracle Mile and Giralda business and property owners, who have been coping with a bump in vacancies and what some say is steadily decreasing foot traffic, especially by day.

The cost will be split by taxpayers and downtown property owners, who agreed to a special assessment through the Coral Gables Business Improvement District. The project also means significant infrastructure upgrades, including a new water main and drainage and electrical-system improvements.

Some longtime Mile merchants say the redo, which the city has been considering for a full decade, is long overdue. The city last refreshed Miracle Mile and its sidewalks in 1999, when medians planted with big palm trees were added. While the work did improve the street’s ambience, merchants say, it didn’t go far enough and was of less than top quality.

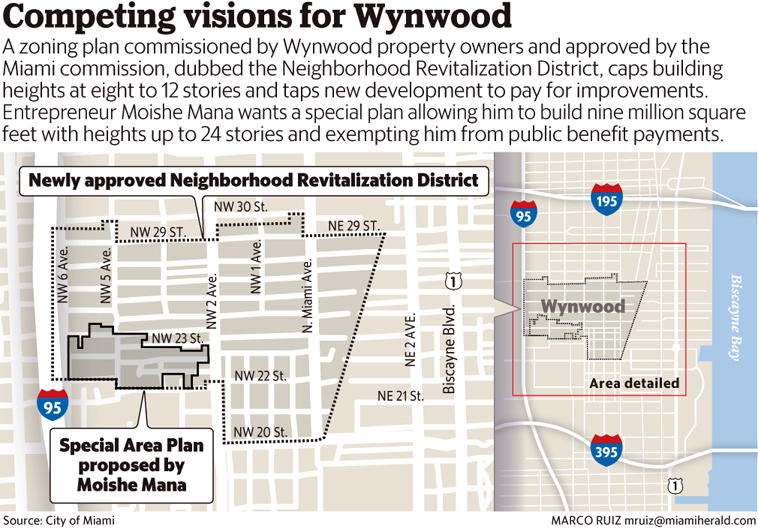

Meanwhile, competition from online shopping, new upscale malls and emerging walkable, hip neighborhoods like Brickell and Wynwood sucked patrons away from the Mile. And though a scad of new restaurants has brought new life after dark, it needs even more activity to thrive, said Jose Bolado, co-owner with his brother Carlos of Bolado Clothiers, on the street for 47 years.

The crowds that will be drawn to the outdoor cafes made possible by the wider, more appealing sidewalks will in turn attract even more people, Bolado predicted. And more people on the street means more customers for retailers who figure out how to entice them into their stores, he said. That won’t happen if the Mile remains as it is, he said.

“Is it necessary? Yes,” said Bolado of the makeover. “All you have to do is walk outside and see the sidewalks are a raunchy mess. The traffic is menacing. It’s a sad state of affairs.”

But the project, which coincides with a wave of high-density development in and around the downtown Gables that’s prompted a backlash from some residents, has also given rise to worries that it will take Miracle Mile down the same path as Lincoln Road, where rising rents have pushed aside local merchants, restaurateurs and customers in favor of big chains catering to tourists.

Some fear that the small streetfront shops that have defined the Mile since its inception in the late 1940s will give way to bigger, snazzier development, like the massive residential and commercial building housing the Tarpon Bend restaurant which replaced a low-scale retail strip more than a decade ago, altering the street’s historic character.

Though Gables founder George Merrick built the Mediterranean-style Colonnade building on Coral Way in 1926, he centered his business district several blocks north at the intersection of Alhambra Circle and Ponce de Leon Boulevard, said historian Arva Moore Parks, author of a new Merrick biography.

It wasn’t until just after World War II that businessman George Zain and his wife Rebyl, turning away from Merrick’s mandated Mediterranean style, established an auto-oriented commercial strip in a spare modern style along a half-mile-long stretch of Coral Way that the city renamed Miracle Mile in 1955. Few of the new buildings were architecturally distinguished, Parks said, aside from exceptions like the Miracle Theater, but the Mile was defined by a uniform low scale.

It thrived as an upscale shopping and business district, a rival to Lincoln Road, until, like its Beach counterpart, it began to lose its allure — and its shoppers — to new suburban shopping malls in the 1960s. For years afterwards the Mile was sustained largely by the bridal and jewelry trade.

Now some long-established shopowners who are hanging on despite declining business fear the streetscape will usher in a transformation they won’t long survive.

“Some day this little strip of shops will be gone,” said John Albright, manager and former owner of one of the oldest businessess on the Mile, Gables Coin & Stamp Shop, while gesturing around at the narrow store, one of several with angled fronts in a plain one-story building. “Just look around. You can see what’s probably coming.”

Already, Albright said, rising rents have pushed out some local businesses, including the jewelry store across the street, which couldn’t afford the $15,000 monthly rent, while a handful of casual-dining chain outlets, such as California Pizza Kitchen and Panera Bread, have opened on the Mile.

Albright and new owner Pat Olive say they’re not sure if they’ll benefit from the sidewalk redo. They’re worried business will be hurt during construction, even though work will proceed in sections and the city promises access to shops won’t be curtailed. They say wider sidewalks might boost restaurants without doing much for a daytime business like theirs that caters to a specialized collector base.

Then there’s the issue of parallel parking. The shift from angled parking will eliminate 96 streetside spaces out of the current total of 236 along the Mile, said Gables public works director Glenn Kephart. And while the city points out that there are hundreds of parking spaces in public and private garages directly behind the Mile’s storefronts, some merchants like Albright and Olive say customers prefer to park in the street out front.

Backers of the makeover plan, though, say that’s outmoded thinking. The city promises to make it easier and more appealing for Miracle Mile visitors to find off-street parking. A new signage scheme that’s part of the Mile renovation will point people to garages, and the city hopes to enhance the unalluring mid-block “paseos” that lead to them, Kephart said. A system of valet stations on the Mile will be expanded. Planners are also exploring phone apps that can give real-time information on parking availability. Meanwhile, the city is going out for bids to redevelop two dingy, outdated garages on the south flank of the Mile.

“We’re going to find our cars are gonna end up where they should be, in garages,” said Stephen Bittel, chairman of Terranova Corp., an early investor on Lincoln Road that’s also one of the biggest landlords on the Mile. “Streets are for people. Great streets are great places for people to gather and walk and shop and eat. That requires wider sidewalks and space for chairs and tables and more modern lighting and different landscaping. That’s what is required for this leap forward. Miracle Mile is the absolute face of the city. It just needs to reclaim its glory and kind of go back to the future. And we think the streetscape is the right way to get there.”

Bittel and BID leaders readily concede that increasing property values, rents and the quality of tenants along the Mile is one important goal of the plan.

But they insist that doesn’t mean Miracle Mile will turn into Lincoln Road. Bittel doesn’t believe the Mile will ever command the kind of rents, now surpassing $300 a square foot, that Lincoln Road does. In any case, he says the success of Miracle Mile will hinge on the right combination of national tenants and local, one-of-kind retailers and restaurateurs that will appeal to Gables residents, downtown workers and tourists.

And while some small shops may have to leave the Mile, they can move to nearby streets, as several already have.

“We’re not trying to compete with South Beach or make it a playground for 20-year-olds,” said Gus Fonte, the BID secretary. “We’re trying to make it a better destination and attract additional development, while keeping workers after dark and giving residents something they can be proud of.”

That sounds like the right formula to Sara Zamikoff, owner of the eight-year old Emporium, a women’s boutique whose mix of clothing and accessories by local and independent designers has won it a dedicated following. She moved her store to the Mile from Ponce de Leon in June in search of healthier foot-traffic, with just a small increase in rent. So far, she’s delighted with the results, and says she’s looking forward to the wider sidewalks and beautified streetscape.

“I see a lot of potential,” Sara Zamikoff said. “Miracle Mile is well known. It used to be known for wedding boutiques, but that’s changing. We are what Lincoln Road no longer is. If we can re-create that ambience here, the more we can highlight the local businesses, that womens’ boutique, a great restaurant, a great local wine store like Wolfe’s, with people wanting that connection and those unique items, that will be amazing.”

Source: Miami Herald

Miami Worldcenter Associates, master developer of the project—in collaboration with Forbes Company and Taubman—are developing a pedestrian-oriented streetscape that will serve as the retail focal point of the 27-acre mixed-use development. The official groundbreaking of the retail project and the Paramount condo project are set for March.

Miami Worldcenter Associates, master developer of the project—in collaboration with Forbes Company and Taubman—are developing a pedestrian-oriented streetscape that will serve as the retail focal point of the 27-acre mixed-use development. The official groundbreaking of the retail project and the Paramount condo project are set for March.