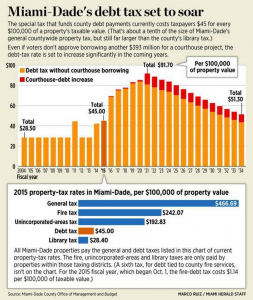

Miami-Dade’s debt tax will soar in the coming years, even if voters reject a $390 million borrowing plan for a new courthouse, according to county forecasts.

Without a dollar of new debt for the judiciary, county forecasts show the special property tax that pays for the county’s debt is set to jump by about 50 percent in 2016. That’s thanks to the arrival of new debt that voters already approved for the county-owned Jackson hospital system, as well as rapidly increasing borrowing costs tied to a nearly $3 billion bond program that voters approved in 2004. “I can’t borrow money without having an impact on taxes,” said Ed Marquez, deputy county mayor for finance. “There is no free lunch.”

Currently costing $45 for every $100,000 of a property’s value, the debt tax funds borrowing approved by Miami-Dade voters and generates the revenue behind a wide portfolio of construction projects. This year it is backing about $1.4 billion in borrowed funds used to create the new Pérez Art Museum Miami, expand county park facilities, build the Miami-Dade police headquarters, dig a tunnel to PortMiami and back hundreds of other projects. It also would allow Miami-Dade to borrow $75 million for an economic-development grant program that Mayor Carlos Gimenez wants to use to provide $9 million for the SkyRise Miami project.

Even with property values rising more than 5 percent annually, a county forecast shows the debt load will get expensive enough that the tax will need to grow next year to $69 per $100,000 of value. That’s about a 50 percent increase. By 2020, it would cost $84 per $100,000 — about 85 percent higher than it is today. Like all property taxes, the debt tax is technically levied in “mills” per $1 of taxable assessed property value. One mill is one-tenth of a cent. The current debt-tax rate is 0.45 mills, which amounts to 45 cents for every $1,000 of value, or $45 per $100,000.

Even with property values rising more than 5 percent annually, a county forecast shows the debt load will get expensive enough that the tax will need to grow next year to $69 per $100,000 of value. That’s about a 50 percent increase. By 2020, it would cost $84 per $100,000 — about 85 percent higher than it is today. Like all property taxes, the debt tax is technically levied in “mills” per $1 of taxable assessed property value. One mill is one-tenth of a cent. The current debt-tax rate is 0.45 mills, which amounts to 45 cents for every $1,000 of value, or $45 per $100,000.

In an interview, Gimenez said the county’s conservative real-estate forecasts could mean the debt tax won’t have to go up as much as forecast. “Hopefully that tax rate can go down in the future,” he said. “I would like to keep it as low as possible. But it’s how much we borrowed versus what the tax base is.”

Even with the forecast increase, the debt tax would remain a sliver of the average tax bill. The current debt tax rate is one-tenth the size of the general property tax rate of $466 per $100,000, which funds police, parks, social services and other core county services. “It’s kind of a footnote on the tax bill,” said Terry Murphy, a former County Commission staffer now working as a consultant for unions and other groups. “I don’t think anyone pays any attention to it.”

Still, the debt tax is already far larger than the county’s library tax, which is $28 per $100,000 of taxable assessed value. The debt tax also played a role almost five years ago in propelling Gimenez into the mayor’s office.

In 2011, then-Mayor Carlos Alvarez’s budget boosted the debt tax more than 50 percent — from 0.29 mills to 0.45 — in order to combat the sharp drop in revenue brought on by the collapse of South Florida’s real estate market. The move violated a pledge county leaders made in 2004 to keep the rate below 0.40 while campaigning for the $2.9 billion Building Better Communities program. The BBC initiative, passed handily by voters, still accounts for the vast majority of borrowing costs funded by the debt tax.

Gimenez, at the time a county commissioner, joined a minority opposing the debt-tax hike. “It’s important to keep your word,” Gimenez said of the 2004 pledge. When he won election after voters recalled Alvarez in 2011, Gimenez rolled back his predecessor’s tax increases, including a reset of the debt tax to the prior year’s level.

The debt-tax relief didn’t last long. Last year, Gimenez proposed a hike to 0.42 mills as part of a larger tax increase to boost spending on fire, libraries and animal services. Facing a political firestorm, the mayor backed off on the tax-hike push for services, but the debt-tax increase survived. With little fuss, it increased a tiny bit again in the 2015 budget year, which began October 1.

In a recent interview, Gimenez said the real estate crisis and voters’ desire for the BBC projects left Miami-Dade with no choice but to move past the ceiling mapped out during the housing boom. “I’m a low-tax, no-increase kind of guy,” he said. “But I do believe in infrastructure. [It’s] one of the things that separates us from the Third World.”

One reason the debt tax tends to avoid the firestorm that follows even tiny increases in other property taxes is the fact that it pays off debt previously endorsed by voters. And while the county mayor and commissioners decide every 12 months when to borrow the money and where to set the tax, the actual rate is driven by debt incurred in prior years.

On Nov. 4, voters may authorize borrowing up to $393 for a new courthouse. But it would not be until 2021 that commissioners would need to increase taxes by a noticeable amount to pay back the money, according to the forecast prepared by the county budget office.

The $393 million sought for replacing Miami-Dade’s moldy and cramped 1928 civil courthouse with a new facility in downtown Miami is equal to about 25 percent of the tax’s current debt load.

With the forecast debt-tax rates, new courthouse borrowing would, on average, push up the tax an additional 8 percent during the next 20 years — about $5.50 for every $100,000 in value, according to county projections. (Over 30 years, the courthouse bonds would cost an average of $7 for every $100,000 in value, according to the forecasts.) “When you look at the average value of a house, it’s so tiny,” said Katy Sorenson, a former county commissioner now running a Miami-Dade panel overseeing spending on the BBC program. “It’s an investment in the future. It’s for future generations.”

The entire courthouse debt would cost Miami-Dade an average of about $24 million a year to pay back through 2045, according to the forecasts. In all, the payments, with interest, would total $733 million over 30 years.

Ballot items allowing Miami-Dade to incur debt for projects are typically called bond programs, since governments borrow money by selling bonds on Wall Street. Investors make a profit on the interest payments that governments pay bond holders, and those payments come from the debt tax.

Bond payments for Jackson account for about 35 percent of the debt-tax increase in 2016. The rest comes from increased borrowing costs tied to the $2.9 billion BBC program. Without a larger tax roll, Miami-Dade can control the tax only by delaying existing payments or scrapping future borrowing.

Esteban “Steve” Bovo, one of two county commissioners to vote against the courthouse plan, said Miami-Dade shouldn’t minimize the impact of a debt-tax increase. “There’s a reality that the number many of us think is insignificant is significant to others,” he said.

Advocates of the courthouse plan say Miami-Dade’s justice system desperately needs the money to replace the existing facility, which has half the courtrooms needed for all 40 judges and leaks to the point that some areas are closed because of mold contamination. “This is a crisis situation,” said Commissioner Sally Heyman, who joined the majority of the 13-member commission last month to send the courthouse item to voters. “It’s become a situation of: Do we invest in ourselves?”

Of the $393 million sought from voters, about $25 million is slated for repairs to the existing building so it can last the five years needed to build a replacement. Opponents of the courthouse plan say Miami-Dade already has about $78 million available for repairs, and argue the delay should be used to craft a more thoughtful strategy for replacing the current facility.

The $78 million would also come from the debt tax, since the money was earmarked in the original 2004 BBC plan for court facilities. Borrowing it would also contribute to a tax increase, though the extra debt is wrapped into the current county forecasts. “Something has to be done,” said Joseph Serota, a Miami lawyer helping the new-courthouse campaign. “The longer we put it off, the more expensive it is.”

Scattered polling shows the courthouse issue faces an uphill climb with voters, and one challenge is the unusually blunt language that county commissioners inserted into the ballot item. It states that issuing the courthouse bonds means “potentially increasing property taxes.”

The phrase “property taxes” did not appear in the other major bond items passed by voters during the past 10 years. Neither did the concept of any tax actually “increasing.”

The 2004 BBC ballot questions talked of “bonds … payable from ad valorem taxes.” A $1.2 billion borrowing plan for the county school system, which has its own debt tax, asked voters in 2012 to approve bonds “secured by the full faith and credit and ad-valorem taxing power of the district.” The Jackson question last year wanted permission to issue bonds “payable from ad valorem taxes collected in Miami-Dade County.”

Latin for “to the value,” ad valorem is essentially the legalese equivalent of property taxes. All three ballot questions passed easily.

Jorge Luis Lopez, a County Hall lobbyist and a lawyer helping run the courthouse campaign, said the tradition of leaving “property tax” out of past ballot questions made them less challenging to pass. “We’re the first,” he said. “We may have to pay a price for that.”

Source: Miami Herald